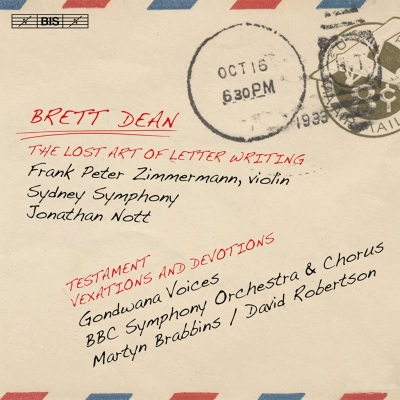

Brett Dean: The Lost Art of Letter Writing; Testament; Vexations and Devotions

The Art of Communication in the Media Age There is scarcely any other composer who can equal Brett Dean in using music to tackle the political and social themes of his era – themes such as the effects of the allpow erful media (as in Game Over), ecological problems (Pas toral Symphony and Water Music) or Aids (Ariel’s Music). The dangers associated with the erosion and misuse of language, and the various – sometimes problematic – aspects of human com munication are a common factor in the works on this recording. In his violin concerto The Lost Art of Letter Writing, which was awarded the re - nowned Grawemeyer Award for Musical Composition in 2009, Dean turns his atten - tion to a form of communication which, for all its individuality and tangibility, is in danger of dying out. The fact that nowadays we are contactable everywhere and at any time not only influences the number of our contacts but also has a decisive effect upon the quality of our interaction with them. In our fast-paced time, when commercial aims and the streamlining of public interests are more important than personal expe - rience and emotional depth, words rapidly grow empty and communication be comes one-dimensional. With his violin concerto, Dean strikes a blow for written cor respon - dence – imaginative, rich in associations and highly personal – without erecting a memorial to it or treating it as a museum exhibit. On the contrary he demonstrates how, even today, the art of letter writing, the conveyance of wholly individual mood pic tures, is possible. Each of the four movements is prefaced by a quotation from an historical letter, like a motto; the movements themselves are lab elled with the place and year of the letter in question. The first movement, ‘Hamburg, 1854’, is based on an excerpt from a letter by Johannes Brahms to Clara Schumann dated 15th December 1854, in which, drawing on a tale from 1001 Nights, he writes: ‘Would to God that I were allowed this day instead of writing this letter to you to repeat to you with my own lips that I am dying of love for you. Tears prevent me from saying more.’ This allusion and Brahms styling himself as the brahmin Ebn Brah are all the more interesting when we bear in mind that Brahms owned a copy of the tales with the dedication ‘To my profoundly revered Johannes Brahms, in thankful remembrance of the marvellous, magical sounds of his Ballads, from Clara Schumann, Hamburg, 8th November 1854’. There is also the occasional flash of a direct quotation: the demisemiquaver accom - pani ment at the beginning alludes to the second movement of Brahms’s Fourth Sym - phony. The piano’s later demisemiquaver figure is a direct quotation too, this time from the Schu mann Variations, Op. 9. In this way Dean spans Brahms’s entire output, from 1854 until his late music – his last symphony. The violin part is often marked ‘Wistful’, and its mood is at times reminiscent of Brahms’s own Violin Concerto. The second movement refers to a letter written by Vincent van Gogh in The Hague on 19th September 1882 to his fellow-painter and mentor Anthon van Rappard, reflecting upon the eternal beauty of nature as being a constant in his otherwise trou - bled and notoriously unstable life. ‘My intercourse with artists has stopped almost completely, without my being able to explain precisely how and why this has come about. All kinds of eccentric and bad things are thought and said about me, which makes me feel somewhat forlorn now and then, but on the other hand it con cen trates my attention on the things that never change – that is to say, the eternal beauty of nature.’ This introverted movement, which Dean himself has described as ‘prayerlike’, evokes the situation of the 29-year-old van Gogh, who had lived in the Hague since 1881. In 1883 he ended his relationship with his model Sien (Clasina Maria Hoornik) and thereafter kept his resolution to be ‘dead to everything except my work’. The third movement, ‘Vienna, 1886’, is a brief intermezzo based on a letter from Hugo Wolf to his brother-in-law and friend Josef Strasser, in which he declines to become godfather to the latter’s child: ‘It grieves me, but I know now for certain: that it is my lot to hurt all those who love me, and whom I love.’ This quotation from a composer who was gradually descending into madness had previously been set to music by Dean as the second of his Wolf-Lieder. In the fourth movement we leave Europe behind and turn to Brett Dean’s home - land, Australia. ‘Jerilderie, 1879’ refers to a detailed letter written by the outlaw Ned Kelly in which he maintains his innocence and lends emphatic expression to his desire for justice. ‘It will pay Government to give those people who are suffering innocence justice and liberty, if not I will be compelled to show some colonial stratagem which will open the eyes of not only the Victorian Police and inhabitants but also the whole British army and no doubt they will acknowledge their hounds were barking at the wrong stump… I do not wish to give the order full force without giving timely warn - ing but I am a widow’s son, outlawed and my orders must be obeyed.’ In terms of sonority, too, this movement is in another world. The constantly intensifying moto perpetuo and the harsher, more acerbic sound that arises from the rather disparate orchestral writing, the stronger emphasis on the percussive aspect and the pallid, rather noise-like woodwind chords are all, according to Dean, in fluenced to some extent by the aridity and strength of this landscape from Australia’s Kelly Country. Testament, written in 2002 for Brett Dean’s former colleagues, the 12 violas of the Berlin Philharmonic, is also inspired by the written word: Ludwig van Beethoven’s famous Heiligenstadt Testament, which dates from October 1802 when Beethoven was still in shock following the diagnosis of incurable hearing loss. Dean’s first inspiration came from his conception of the sound made by Beethoven’s pen, scribbling with fever ish haste on the paper. A single look at Beethoven’s manuscript – often almost illegible, full of crossings-out and ink blots – conjures up a noise to one’s ‘inner ear’, and at the beginning of the work Dean has tried to imitate this by means of finely facetted agitation, played using bows without rosin. The result is a nervous, diffuse and veiled sound image; optically, however, the sound heard in concert does not cor - respond at all with the visibly forceful exertions of the musicians. On another level, Testament traces the fluctuating emotions in Beethoven’s text. Hectic activity alternates with soaring cantilenas; calm passages are constantly interrupted by violent out bursts – just as Beethoven’s text wavers be tween sorrow, anger, despair and self-pity. In be tween, fragments from Beethoven’s ‘Rasumovsky’ Quartet, Op. 59 No. 1, keep appearing – a work composed four years after his stay in Heiligenstadt. These quota tions, however, are always swiftly covered over, and merely suggest a way out of a situation that, for Beethoven, was without pros pects. By using this technique of for mu lating non-con - tem porary material in a con temporary way, Dean succeeds in musi cally inter preting the time in Heiligen stadt as a turning point, a move from the deepest despair into one of Beethoven’s most important creative periods. Vexations and Devotions, described by Dean himself as a ‘sociological cantata’, deals with the dehumanization of society, which is closely bound up with the loss of language and an increasing sense of alienation. The first movement, Watching Others, sets the scene with a restless, diffuse orch - estral sound, rumbling in the lowest register. From this the choir finally emerges with music of such calm and beauty that it gives lie to the text: ‘The loneliness of watch ing others on television…’ The words, by Dorothy Porter, are characterized by the hope - lessness and loneliness of the individual in today’s world, most forcefully expressed in this image of the passivity whereby, spellbound, we follow unfamiliar, ficti tious lives on television, whilst at the same time neglecting our direct contacts with living people. In the gaping hole between fiction and reality, all that remains for us is lone liness, which we perceive as all the more painful. In Bell and Anti-Bell the electronic sound of a pre-recorded telephone queueing message is code for alienation in our modern communications systems. The text arose from a collaboration with the Australian poet and cartoonist Michael Leunig. Its bitter, satirical dramaturgy moves from the soul-destroying rhetoric of the telephone queue, via the incongruous and misunderstood hymn Sweet Secret Peace, through to the sys - tem’s eventual collapse: in the end it is derailed and begins to question itself and every thing around it. The problem of a language that no longer says what it means, or even consciously creates false associations, gives rise to the concept that underlies the third movement, The Path to Your Door. Here Dean has compiled empty phrases, so-called ‘weasel words’, of the type that is all too familiar from the mission statements of various organizations. He contrasts these with Leunig’s poem The Path to Your Door, which forcefully presents joy and sorrow as inseparable constituent parts of human relation - ships. The innocence and purity of the children’s voices allow no doubt as to the verac ity of the message and provide the work with a hopeful, positive conclusion. Dean confirms this musically: the defining three-note motif of The Path to Your Door, with which the movement begins, is identical to the first main motif of the violin con - certo. Our longing thus remains alive and unappeased. © Antje Müller 2013

专辑歌曲列表

-

Martyn Brabbins、BBC Symphony Orchestra 14324702 14:55